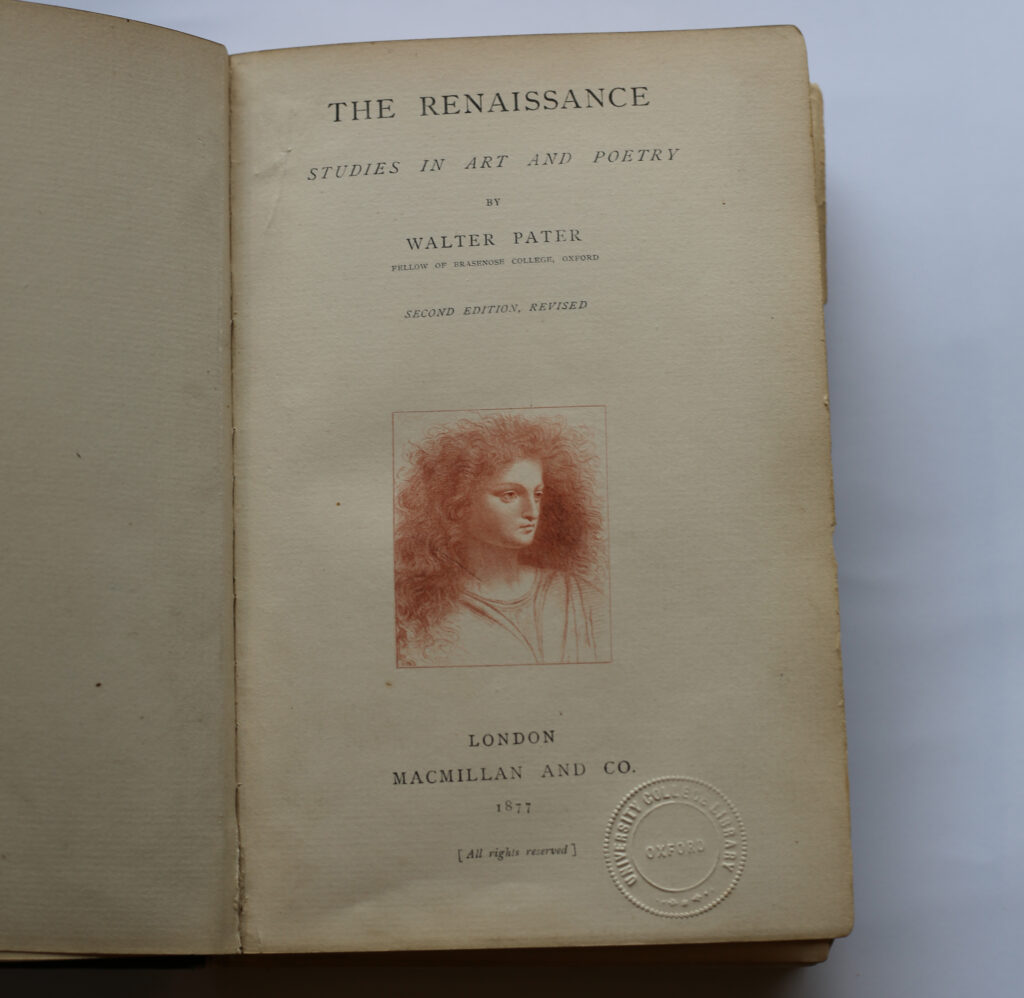

Christian Cole, Alain Locke and Oscar Wilde were students at University College, Hertford College and Magdalen College, respectively.

All three men studied Literae humaniores, and all three read one of the age’s most provocative books, Walter Pater’s Studies in the History of the Renaissance.

Written by a reclusive Brasenose tutor who lived with his sisters, the 1873 praise of aestheticism and hedonism quietly detonated a bombshell in the City of Dreaming Spires. A year after it was published, the Master of Balliol College, Benjamin Jowett, suppressed the scandal of Pater’s relationship with an undergraduate known as “the Balliol Bugger.”

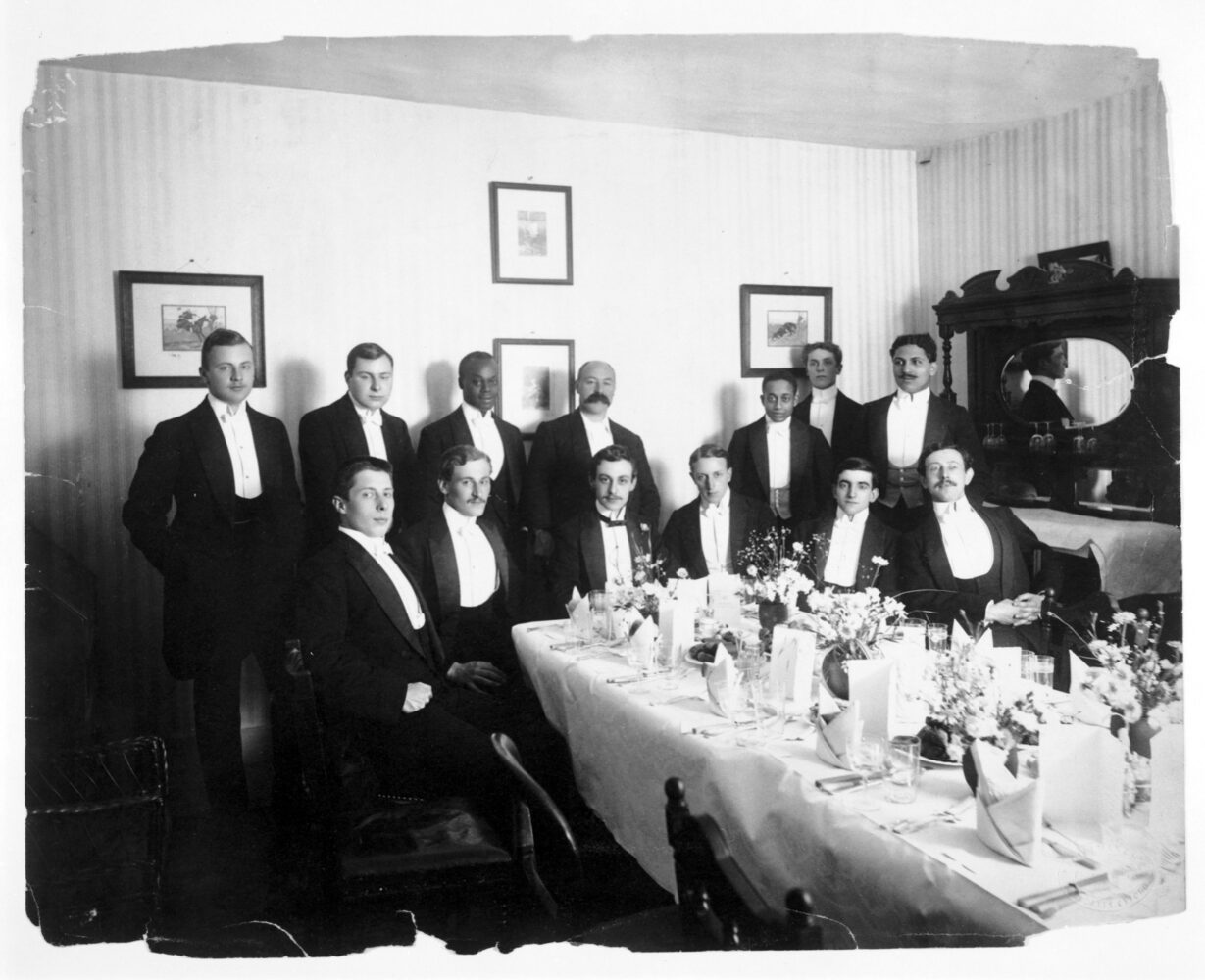

University College’s copy of Walter Pater’s Renaissance: Studies in art and poetry (2nd rev. ed., 1877), probably the same copy that Christian Cole borrowed as a student. Courtesy of the Master and Fellows of University College Oxford: YHQ/PAT.

T. Shrimpton, ‘Aesthetical Ecstasy’ from 1224 caricatures of Oxford life, G.A. Oxon 4o 415, fol. 755.

Reproduced by kind permission of The Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford.

Pater told Renaissance readers to direct their attention to the most exquisite moments of their lives, reminding them that life was short. We only have “a counted number of pulses” to live. Carpe diem, Pater implied. An advocate of art for art’s sake, Pater left some doubt as to whether exquisite moments were to be found only in art or whether they might also be pursued in pleasures of the flesh.

Since the sixteenth century, sodomy had been a crime in England punishable by the death penalty. In 1861, the punishment was reduced to imprisonment for 10 years to life. Over the centuries, men who loved men had found ways around this. By the Victorian era, shared labour and passionate idealism, muscular Christianity and Greek friendship had become encoded into a romantic pattern of discreet signals for love between men.

Cole borrowed Pater’s Renaissance from his College library in 1877.

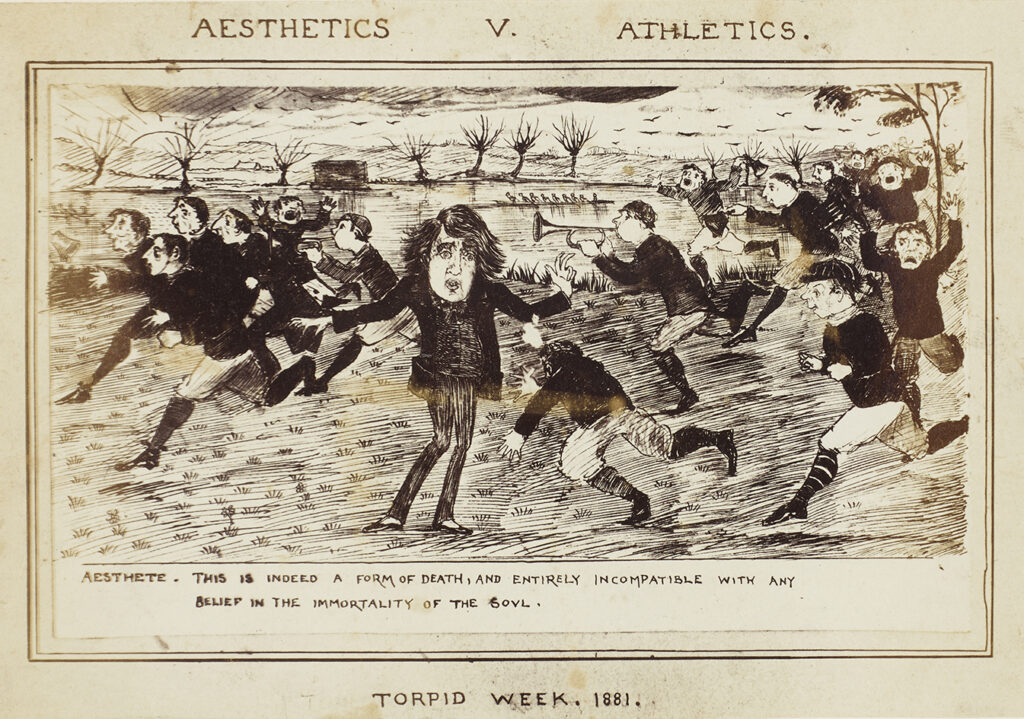

T. Shrimpton, ‘Aesthetics v. Athletics’ from 1224 caricatures of Oxford life, G.A. Oxon 4o 415, fol. 725. Reproduced by kind permission of The Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford.

Gay readers like Wilde and Locke may have felt that Pater validated their aesthetic philosophy and preferred sexual orientation. Both came to admire the Greek model of love. Oxford’s homosexual community had to be relatively circumspect, but Locke enjoyed his social life here. “Let me tell you about the men,” he wrote a friend, “I have met some of the best specimens.”

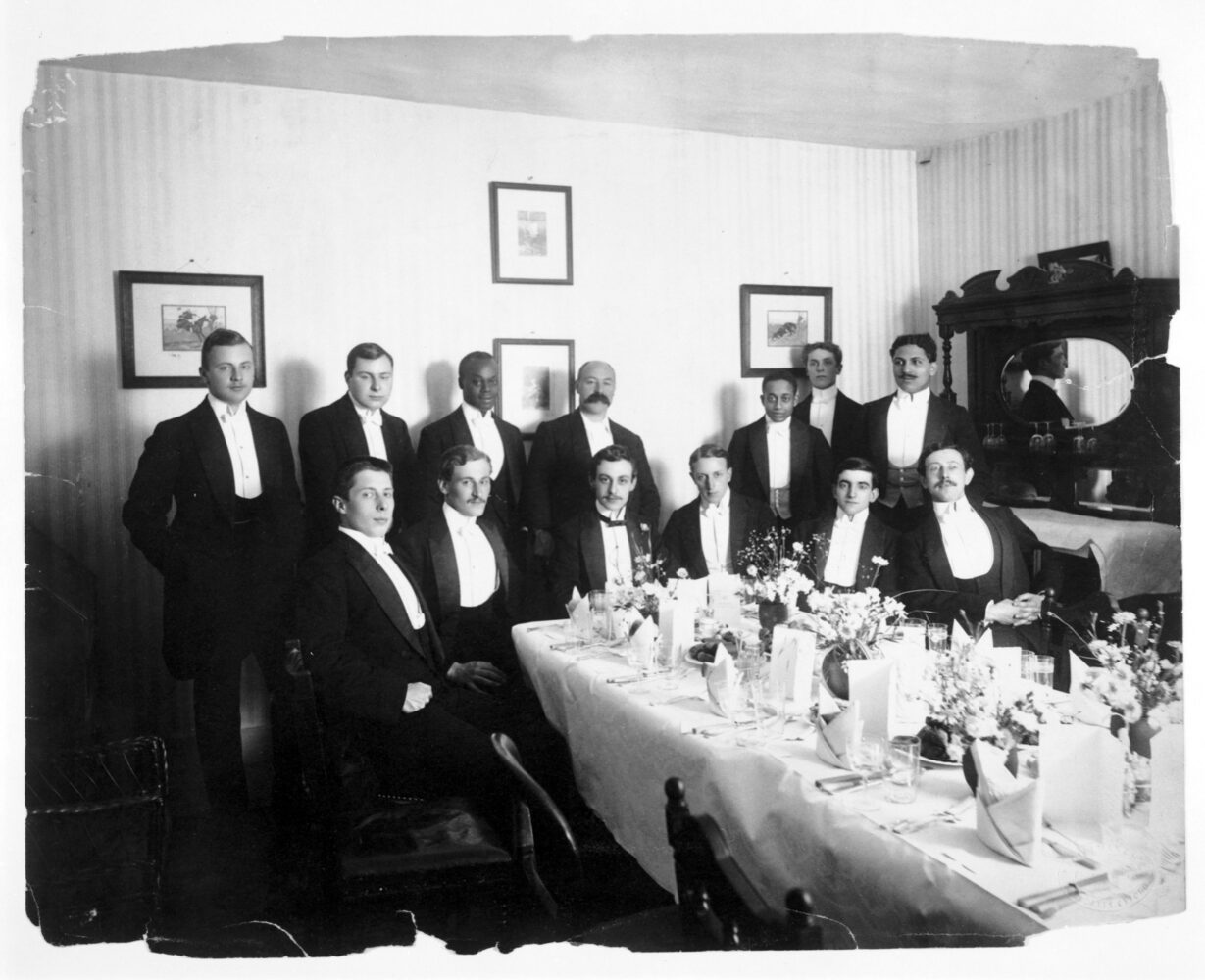

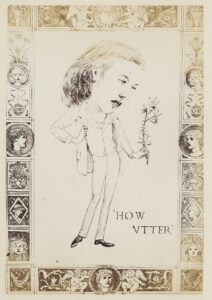

T. Shrimpton, ‘How Utter’ from 1224 caricatures of Oxford life, G.A. Oxon 4o 415, fol. 706.

Reproduced by kind permission of The Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford

The Renaissance combined youth, beauty and homosexuality into a succinct countercultural code: Aestheticism. Here was the philosophy Wilde would spend a lifetime making his own. In 1890s London, at the height of his decadent phase, Wilde surrounded himself with men. Locke did the same in 1920s Harlem, drawing notable Black gay artists including Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Wallace Thuman and Bruce Nugent.

“Things of beauty,” Wilde scrawled in his Oxford commonplace book, “come in a scheme of the noblest education.” The aesthete-in-training lived lavishly. “I bought Venetian glass when I was at college, and for the first term my servant broke one glass every day, and a decanter on Sunday,” Wilde said, “but I persevered in buying them, and during the succeeding terms of my whole stay at college he did not break a single piece.” Wilde’s Magdalen rooms became an exotic setting for his parties. With decorations of blue-and-white china, artistic bibelots, statuettes and photos of the Pope and Cardinal Manning, the effect was eccentric and – crucially for a young man determined to impress – memorable. “How Utter”, indeed. In the video below, Prof. Nicholas Shrimpton discusses Wilde’s relationship to Aestheticism:

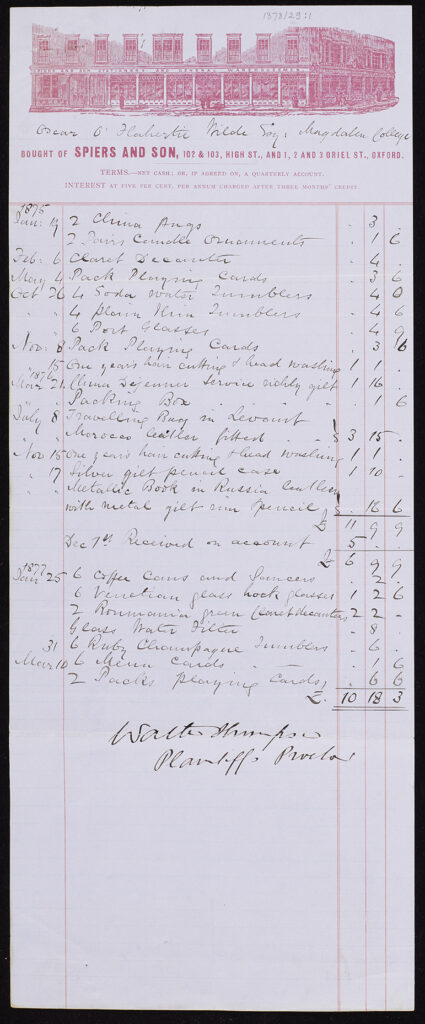

Such extravagance did not come cheap, as Wilde’s Spiers & Son’s bill reveals. The Oxford High Street merchants logged his 4 packs of playing cards, Venetian glassware, travelling cases and haircuts. Debt was to be a long-running theme in Wilde’s undergraduate life, as it was in Locke’s.

Oscar Wilde’s bill and summons from Spiers & Son.

Reproduced by kind permission of The Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford: OUA CC papers 1878/29:1.

“Let me tell you how we live,” Locke wrote to his mother in 1907, breathlessly detailing the furnishings of his Hertford College room (a sofa and chair, “electric chandelier”, writing desk, oak piano and a sideboard “for food and wines”) and daily routine. At 7:30 a.m., his scout appeared, wished him good morning, lit the fire, and ran a bath.

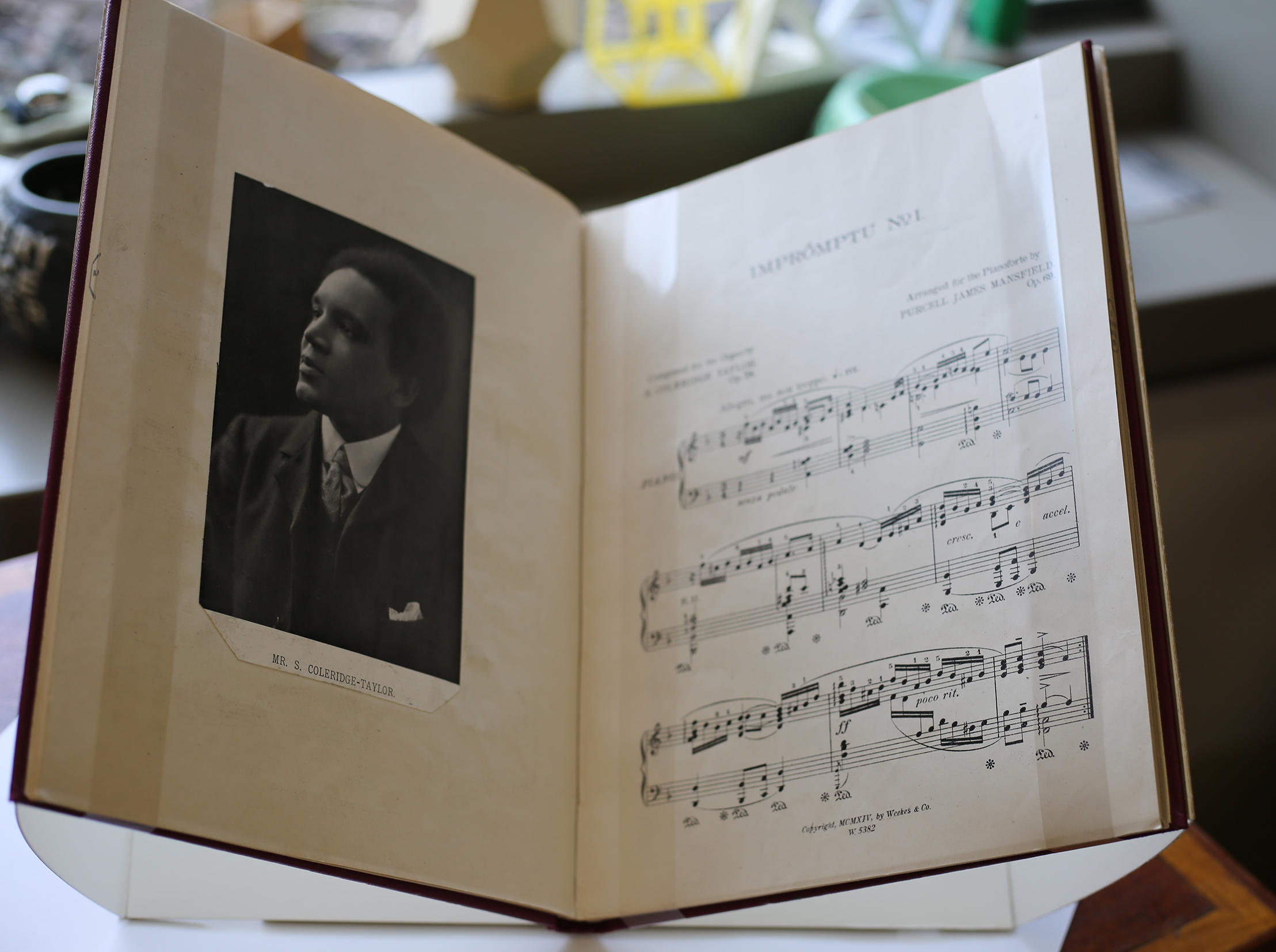

Alain Locke’s favourite composer: Bound volume of music written by Samuel Coleridge Taylor, c.1903-1916.

Courtesy of St Catherine’s College, Oxford: 786 COL.

In later years, Locke coxed for his college and played duets with friends on his rented white baby grand piano. His favourite music was by the Anglo-African composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. You can listen to one of his pieces in the following video, performed by Dr Philip Burnett:

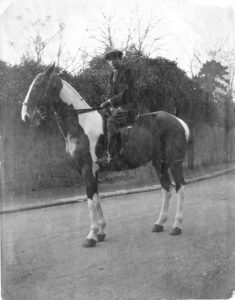

Photograph of Alain Locke on horseback, Oxford, ca.1909.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Moorland Spingarn Research Center, Howard University: Alain Locke Papers, Box 154-207, Folder 17.

Locke befriended Jesus College student Pixley ka Isaka Seme (1881-1951), who had been the first Black South African to study at New York’s Columbia University. The dedicated pan-Africanists soon became fast friends, enjoying French lessons and horsebackriding together. The pair were vital to the establishment of the Cosmopolitan Club, a society for students who shared internationalist interests. It was in the Club’s magazine that Locke began to formulate his criticism of imperialism, writing an epilogue for the first issue in 1908.

Pixley ka Isaka Seme later founded the African National Congress, unifying the Black people but also acting opportunistically for his own enrichment, according to his biographer Bongani Ngqulunga. He remained Locke’s lifelong friend, repeatedly urging him to leave the US and settle in Switzerland. “The native press is ready to carry your message into every home in South Africa,” Seme wrote to Locke to entice him to join his endeavours.

First issue of The Oxford Cosmopolitan (June 1908), the epilogue by Alain Locke: Bodleian Libraries, Soc. 3977 d.56, title-page and pp.15-16.

Reproduced by kind permission of The Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford.

In response to seeing the exhibition, DPhil candidate Vafa Ghazavi discusses Alain Locke’s cosmopolitanism and religious convictions in the video below: